Canine Core Stabilization Exercises

Strengthening the “power center” isn’t just for bipeds

By Jason Smith

Strengthening the core is just as important for dogs as it is for people. Many people ask tremendous things of their dogs – in the ring, in the field, in the water – but there’s only so much that a training program can achieve. The pupil needs to be ready to be trained, too. At a recent sporting dog summit I attended hosted by the dog food giant Purina, much emphasis was placed not on how to train, but on all of the other factors that help canines achieve top performance and prevent injury.

I know I fall into this trap: I want my puppy to just be a puppy and let that sponge of a brain soak things up before the formal training program starts. What he learns will be a function of my ability as a trainer. And what happens to him physically will be a matter of what his genes predispose him to and, well, happenstance.

But there’s a way to begin physically developing young dogs for the challenges they will face in the tasks their owners put before them – even if those tasks are games of tennis ball and Frisbee in the backyard or at the beach. And the dog that is healthier, without nagging injuries, gimps, limps, or unnecessary bumps, will be more ready to learn and to have fun – and to prolong the learning and having fun.

“Core stabilization or strengthening,” says Dr. Jimi Cook, a veterinary orthopedic surgeon at the University of Missouri (and quite a busy guy, as you can tell by the sidebar), “involves specific exercises and muscle training techniques that are aimed at increasing strength, flexibility, symmetry, and endurance of the vital core muscles – the abdominal, spinal, and pelvic muscles. You can think of it as ‘Pilates for dogs.'”

“Core strength” has been the buzz phrase in human fitness for many years, and for good reason. Our core muscles support our back and spine any type of movement and activity we do. When those muscles are weak, other “outlying” muscles – and ligaments and joints and tendons and everything else that supports our skeletal system – must compensate. And they weren’t designed to perform their functions and support the upper body as well. It’s all about decreasing the stress load on the rest of the body, and with a solid foundation at the core, you put yourself – or your dog – on the path toward attaining peak performance. And in a safe manner.

Dr. Cook is passionate about the advantages that a core strengthening program provides dogs, both the performance/working dog, but also the average family pet. “The core is the ‘power center,’ so it is vital for maximizing performance in every aspect – power, speed, balance, control, flexibility, etc. More importantly, though, and in my opinion, is that it is the best way to decrease injury risk.

“The majority of injuries in performance/working dogs occur when – and even because – physiologic fatigue sets in,” Dr. Cook continues. “Physiologic fatigue is when neuromuscular function is diminished even though the dog is not ‘tired’ – that is, the dog is still going full out. This is especially true of the core muscles. Both overuse and acute traumatic injuries occur during or because of physiologic fatigue. So, bottom line, core stabilization is key to safety and success. I do not know of any elite human athletic training programs that do not focus on core strengthening.”

As I sat listening to Dr. Cook’s presentation, the plan for my next pup was already forming. The problem? My Lab Ginny. (About 80 percent of my immediate and extended family just read that and mumbled, “You ain’t lying,” but that’s neither here nor there.) The reason this came up as a problem for her is that she’s three years old already, a new pup is a ways off, and Dr. Cook was suggesting this as a program for younger dogs. So I asked him a few months later, and he clarified: “You can start these as early as possible in a dog’s life. That is the beauty of them – they are very safe, help development a great deal, and add to obedience training as well. [But they are] definitely useful for the dog’s entire life. The earlier the better for long-lasting effects, but absolutely beneficial no matter when you start.” [emphasis added]

Dr. Cook suggests that before you develop a program, clear everything with your veterinarian or a specialist; but as you’ll see, these are safe exercises. Really, they are just some twists on basic obedience training, and further development of normal and sound socialization practices that we all employ when getting a pup used to being handled and our hands on his body.

As to the frequency of the exercises, Dr. Cook says that consistency is key, but that you can mix it up by day, too. “For me, the perfect scenario would be doing them every day – three or four of them one day, and then three or four different exercises on alternating days, if possible. But realistically, if you can do at least three or four of them consistently, at least every other day, that would definitely be beneficial. Less than that and you may not really see the benefits. Remember, they are also ideal as part of a warm-up period before training and performance!”

The exercises below are not listed in a particular order, and you certainly don’t have to do them all every time. As Dr. Cook suggested: three or four one day, and three or four different ones the next day. However, he does think “it is good to keep your own routine/sequence once you decide on it.”

The Exercises

(The following was provided directly from Dr. Cook, and is reprinted here with his permission; the customary “his/her” in reference to the dog has been replaced with “his” for ease of reading.)

All should be done in a controlled manner under your direct observation, ensuring that your dog is on good footing, is not struggling to do the activity, and is not showing any signs of pain during or after the exercise period.

Cookies to Hip

With your dog standing squarely on all four feet, use a treat or toy to entice him to turn his torso to the right so that his nose reaches his rump area without moving his feet. Then do the same thing to the dog’s left. Build up to where the dog holds the position for 20-30 seconds at a time, and do 15-20 repetitions to each side during a session.

Weight Shifting

With your dog standing squarely on all four feet on a non-slip surface with you supporting him, begin to gently sway him left to right. You should not rock your dog so much that he has to move his legs to regain balance. Initially, support your dog as you shift his weight. As your dog gains strength and balance, he will be able to perform these exercises with less support. After doing left to right weight shifting, you can do forward and backward weight shifting in the same session. Build up to where each session lasts 8-10 minutes.

Leg Lifts

With your dog standing squarely on all four feet on a non-slip surface with you supporting him, lift the right hind limb off the ground for a few seconds and then replace it to the ground so your dog is standing squarely again. Then do the same thing with the right front limb, then the left front limb, then the left hind limb. Initially, support your dog as you lift each limb. As your dog gains strength and balance, he will be able to perform these exercises with less support. Build up to where you hold each limb up for 20-30 seconds at a time, and do 10-15 repetitions to each limb during a session.

Front End Wobble

With your dog standing squarely on all four feet on a non-slip surface with you supporting him, place his front feet on an appropriately sized wobble board or balance disc. Initiate and support a controlled teeter-totter movement of the front legs on the board/disc. Initially, support your dog fully during this exercise. As your dog gains strength and balance, he will be able to perform this exercise with less support. Build up to where each session lasts 5-7 minutes.

Rear End Wobble

With your dog standing squarely on all four feet on a non-slip surface with you supporting him, place his rear feet on an appropriately-sized wobble board or balance disc. Initiate and support a controlled teeter-totter movement of the rear legs on the board/disc. Initially, support your dog fully during this exercise. As your dog gains strength and balance, he will be able to perform this exercise with less support. Build up to where each session lasts 5-7 minutes.

Leash Walking

Controlled walking is a very effective core stabilizer, but it is important to understand that it is not “playtime,” and it must be controlled to be effective for this purpose. A dedicated and focused walking period will help your dog gain core strength, flexibility, and endurance. Use a short leash to maintain control of your dog at all times (harnesses are preferred over collars). Changing pace during the walk and including inclines and declines are beneficial. These walks can be as long as you like, as long as your dog is not resisting the activity or showing any signs of pain during or after the exercise period.

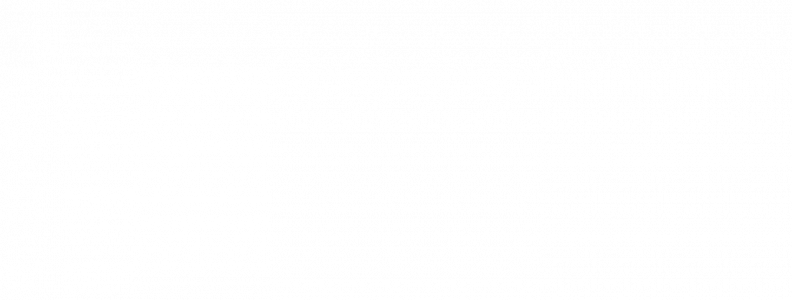

Figure 8 On Hill

Walking your dog in a figure-8 pattern on an incline that has good footing is a great core strengthening exercise as well as an ideal warm-up activity. Use a short leash to maintain control of your dog at all times (harnesses are preferred over collars). Walk your dog in a large (at least 20 feet) figure-8 pattern. These walks can be as long as you like, as long as your dog is not resisting the activity or showing any signs of pain during or after the exercise period.

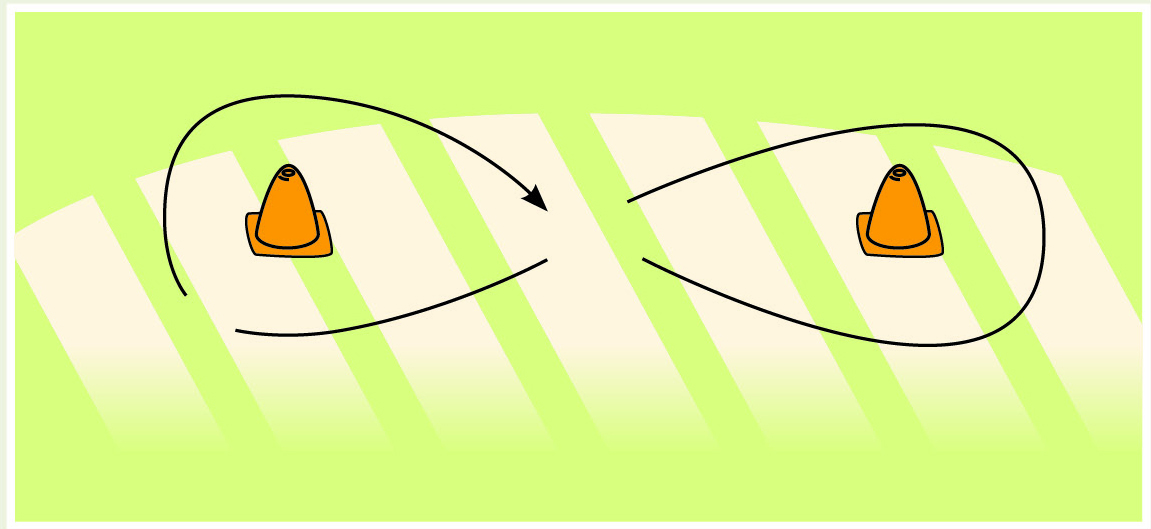

Cone Weaving

Weaving through cones helps to improve balance, function, and strength as well as “muscle memory” for neurologic function. These exercises can be performed by placing cones or buckets in a level area that has good footing. Place each one approximately 3 feet apart. Walk your dog through the course, weaving around each cone/bucket in a figure-8 pattern. Go through the course 4-5 times initially and then build up to 20-30 repetitions per session, as tolerated.

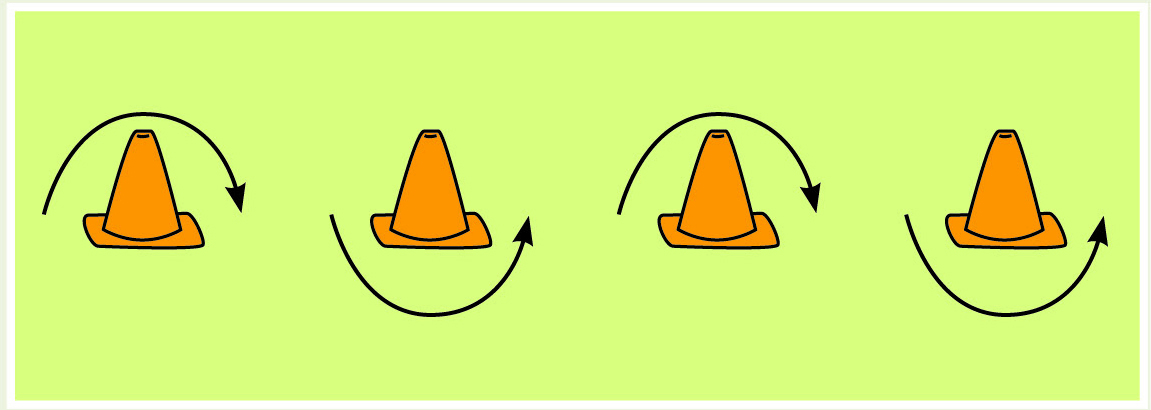

Cavalettis

Walking over Cavaletti poles helps to improve strength, range of motion in the joints, flexibility, balance, and “muscle memory” for neurologic function. These exercises can be performed by placing 4 to 8 pieces of PVC pipe, 2″ x 4″ boards, broomsticks, poles, or similar “hurdles” in a level area that has good footing. The hurdles should be placed to be one body length of your dog apart. Walk your dog through the course, stepping over each hurdle. Go through the course 4-5 times initially and then build up to 20-30 repetitions per session, as tolerated. Controlled walking of your pet through tall grass, elbow-level water, or deep sand can provide similar beneficial effects.

Swimming

It is important to remember that swimming for core stabilization and strengthening is not “playtime” – it should be a controlled, focused, and monitored exercise for a defined period of time. Pools, lakes, or ponds are all acceptable for swimming rehab as long as they are clean enough for you and your dog to swim in. The following “rules” must be followed:

- Always be present when your dog is swimming. Additionally, you may want to consider getting a canine life preserver, at least initially.

- Use extra caution when your dog is entering and exiting the water; it may be slippery! A slip can cause injury. You should be there to help support them every time they enter and exit the water. You may consider laying down a mat that they can get good footing on at the water’s edge.

- Do not force your dog to swim if they are uncomfortable with it.

Swimming can begin with 1-2 minute sessions once to twice daily, gradually increasing up to 15 minutes twice a day if your dog can handle that well.

Water Treadmill

Water treadmill therapy is an excellent core stabilizing and strengthening exercise. However, it is usually reserved for rehabilitation after injury or surgery, or for cases where more traditional core stabilizing exercises are not possible or effective. Water treadmill therapy should only be done under the guidance of a trained veterinary professional.

As we’ve all known for years, training a dog’s mind is not the only part of a training program – there is also a physical conditioning aspect. And it’s common to rev up a conditioning program prior to a dog’s working season, to shed the pounds accumulated from lazing the days away.

But conditioning is not just cardiovascular, and it’s not just achieved from running, running, running. Conditioning the core is done on the small scale, a little bit every day, to not only help attain that peak performance, but perhaps prevent an injury in the years ahead.

James L. Cook, DVM, PhD, DACVS, DACVSMR, University of Missouri: After receiving his undergraduate degree from Florida State University and competing for five years as a professional water skier, Dr. Cook completed his DVM in 1994 and PhD in 1998, both at the University of Missouri. In 1999, he founded the Comparative Orthopaedic Laboratory. He has more than 120 publications, over $20 million in research funding, received numerous awards including America’s Best Veterinarian (2007), holds 14 U.S. patents, and has seen three biomedical devices through FDA approval to human clinical trials.

After 18 years as a veterinary orthopaedic surgeon in the College of Veterinary Medicine, he came to the Missouri Orthopaedic Institute to head the Division of Research as the William and Kathryn Allen Distinguished Professor in Orthopaedic Surgery. Dr. Cook and his wife, Cristi, also a veterinarian, have two dogs and three cats; do puppy raising for New Horizons Service Dogs; and run Be The Change Volunteers, a NGO dedicated to building schools in developing villages whose teams have built 22 educational facilities in 14 countries, providing educational opportunities to more than 4,000 students.