Pointing Dog Pointers: The Slow Learner

POINTING DOG POINTERS JANUARY 2015

By Bob and Jody Iler

No one likes to be labeled a “slow learner!”

And after researching bloodlines, choosing a reputable breeder, and picking and developing a special pup, you sure don’t want to hear that your pup is a “slow learner” either!

When it comes to developing our pointing dogs, if we have misplaced expectations, we may end up disappointed. As trainers, we always sit down with our clients and explain our started dog program, noting that by the end of the program, the client’s pup will likely be hunting, pointing, and handling fairly well. But we always add that all pups learn at their own pace. What is right for one pointing dog “pupil” may not be right for another—just like kids in school. And, like a student in school who blossoms when teaching methods are geared to individual development, the pointing dog pup that develops slower than the “norm” may turn out to be the best dog you’ve ever had, if given the time to learn on his own schedule.

“Slow learners” can be of any pointing dog breed and either sex. The one thing they may have in common is that they seem unsure, possibly a bit soft or timid, and often need more time to assess and acclimate to new conditions. Slow learners may be shy of birds at first, maybe even afraid of the noise of wings whirring as they fly away. They may quit bounding around the field when a checkcord is attached to them and tuck their tails in uncertainty. Slow learners may notice the sound of even a popgun more than the bolder, “quick learner” types. And some pups that seem to come on well in the beginning may “hit a wall” in their training progress for no seemingly apparent reason (although there will always be a reason—if we are willing to look closely and understand what our pup is trying to tell us by his actions).

We want to be quick to note here that these things also describe a dog’s temperament and there are soft, shy dogs that seem to be fast learners, too. Again, each pup, no matter what its temperament, will learn at a pace all its own. Checking all the boxes by a certain age or timeframe is counter intuitive to good pointing dog development. In the old days, many a trainer would often discount a slow learner and advise a client to start fresh with a “better prospect.” We know from personal experience though that it can take months for a dog to come into its own, and giving a dog at least 18 months to two years to do this is not an exercise in futility.

Let’s take a look at two such “slow learners” that we had at our kennel for training in years past.

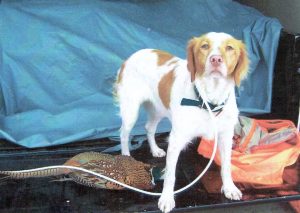

Belle was a tiny little Brittany that we got in for training as a 6-month-old pup. She seemed to be full of contradictions. She liked running about in the field, but quit hunting as soon as we put a checkcord on her. And we needed to have a checkcord on her because Belle also liked to slip out of our line of vision and run away!

It was the same with bird introduction. She seemed to like birds, but ran hot and cold at the start. Belle stymied us with her “on again, off again” demeanor. Checkcord on: no enthusiasm or drive. Checkcord off: run for the hills. We knew one thing for certain. We wanted Belle to become bird crazy and hunt with enthusiasm while on the checkcord. She was too young for e-collar work to remedy her handling transgressions; that would be a sure way to shut her down completely.

By the end of the started dog program, we had ignited the fire within Belle for birds and she hunted well with the checkcord on. Her proud owner was a young man who was dedicated to making her the best bird dog she could be. He was also very willing to listen to our advice for Belle’s first hunting season. “Should I keep the checkcord on while I hunt her?” he asked us. When we said “Yes,” he wondered aloud at the logistics of it.

During the upcoming season, we got regular reports from him on Belle’s progress and the travails of trying to hunt a dog with a checkcord. We have to give much of the credit for Belle’s success to her owner, who spent a frustrating first season hunting his little dog on a checkcord. By season’s end, she was firmly entrenched as a bird dog, and the following spring he brought Belle back for a little “extra” incentive work on handling with the e-collar. Because he was willing to work with Belle at her own pace and follow our advice, he helped his hunting partner come into her own, in her own time.

An even more memorable “slow learner” was a German shorthair pup that came to us at four months of age because the breeder felt the pup just didn’t have the makings of a good bird dog. We offered to take the pup as our own and give him a shot.

The day Buddy arrived was also the day of his first bath, first ride in a truck, and first collar and leash attached to him, before he came to our kennel. Needless to say, he stood miserably in the front yard, tail tucked between his legs, wondering what life was all about. Shy and timid, when we first took Buddy to the field, he proceeded to run right back to our kennel, where his new digs, food, and water had given him some measure of stability to return to. To him, the field and birds were frightening new experiences that he wanted no part of.

So Buddy became our shining example of an exercise in patience, patience and more patience. First he learned to get used to walking around on a long line until he no longer paid any attention to it. (That way we could keep him from running out of the field!) Next, he learned that the field could be a fun place to bound around in, with lots of exciting smells to investigate. And finally, he was slowly and gently reintroduced to birds, and this was probably the longest process of all. We used to joke that we did everything but put on a quail suit and flop around to pique his interest. Day after day, week after week, we slowly advanced, gently persisting with what Buddy would accept, and backing down if we felt we were going too fast.

One day, Buddy “got it.” On a sunny spring morning, on one side of the creek that runs through our field, he scented a spooky quail and the rest was history. He stood immobilized, only his eyes moving—shifting from the area where the quail was, to our faces, and back again. His tail was erect and looked like a bottle brush. His mouth closed, we could see his breath coming through the flews on each side of his mouth. Buddy was on his way.

At the age of 18 months, Buddy was purchased by a client and friend inWisconsin. Over the next decade, hundreds of birds were shot over this “slow learner,” who also returned to our kennel each fall for some bird work fun while his owner fished inMontanafor a month. Besides being a superb pointing dog, Buddy also lived the dream of a pampered, loved house dog. The best argument we can offer for giving a slow learner time is the statement made by Buddy’s owner as the years went by. “If I ever get another dog,” he said, “I want one just like Buddy.”

Now, of course, if Buddy or Belle hadn’t had what it takes to begin with, all the time in the world would not have mattered. But if your pup comes from good stock and seems to be taking the long route to accomplishment, give pup the benefit of good bloodlines and extend the gift of time and training at the pup’s own pace.

Pointing Dog Pointers features monthly training tips by Bob and Jody Iler, who own Green Valley Kennels in Dubuque, Iowa. Bob and Jody have trained pointing dogs for over 35 years and have written many articles for The Pointing Dog Journal.